Simple controller for a 128x32 OLED display from scratch - software I2C with SSD1306

In this topic I will show how to step-by-step run a simple driver for a 128x32 OLED without using off-the-shelf libraries, relying solely on software-based I2C. I will test how difficult it is to display text on such a display and how many bytes of RAM and Flash it requires. Will it be possible to run the text drawing without holding the image buffer in memory? Let's find out!

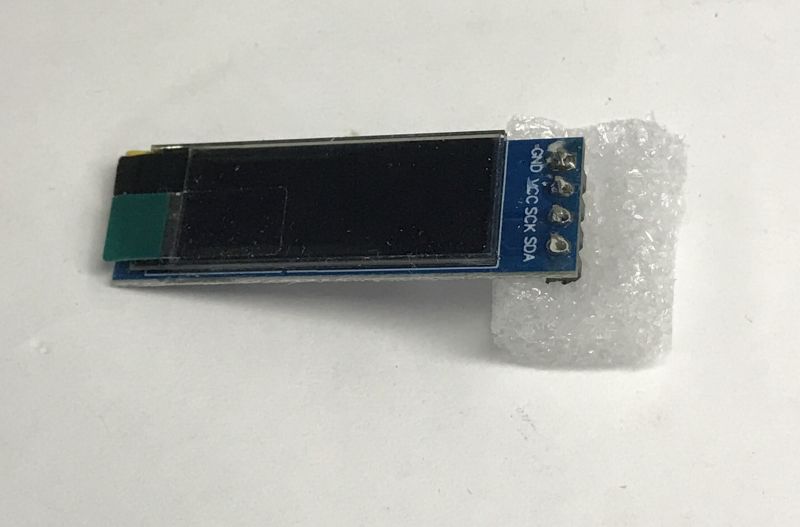

I've shown the SSD1306 before, but I was running it with an Arduino . I described its connection and capabilities there. I was quite happy with the results, for this reason I also decided to add support for this display to my IoT firmware supporting up to 32 platforms .

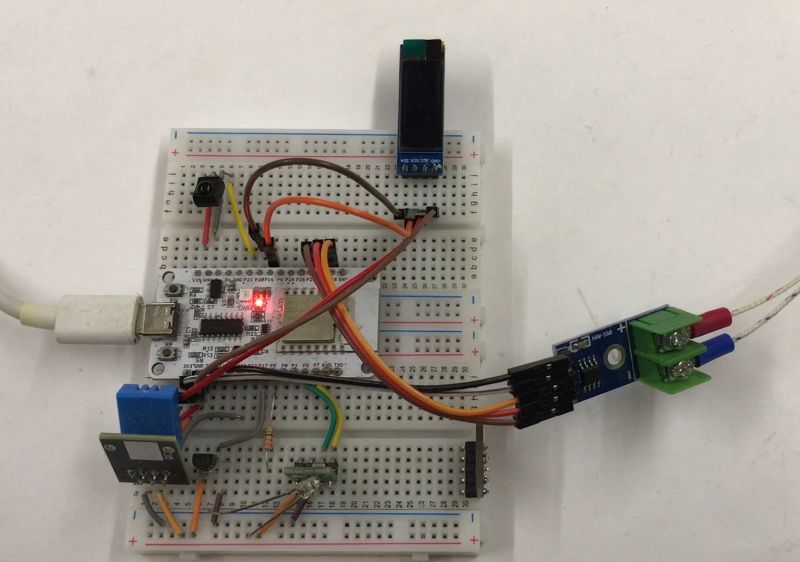

I prototyped the driver on a BK7238, but due to the use of software I2C it should work on any supported platform.

I2C scan

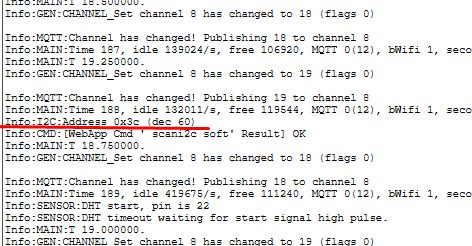

The first thing I run in such cases is an I2C address scan. It allows me to check that everything is well connected and that I have the address of the target device well defined. In my firmware there is a ready command for this - scanI2C . It displays the addresses of the devices found:

Address 0x3C matches the catalogue note, you can proceed to the next step.

First flashing

The second step is always to run the simplest set of operations, the result of which is visible and verifiable. Here I wanted to try blinking the display.

In this case, however, this requires a full configuration of the display and an understanding of its protocol.

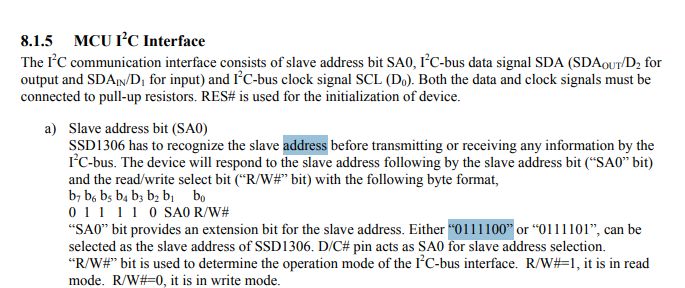

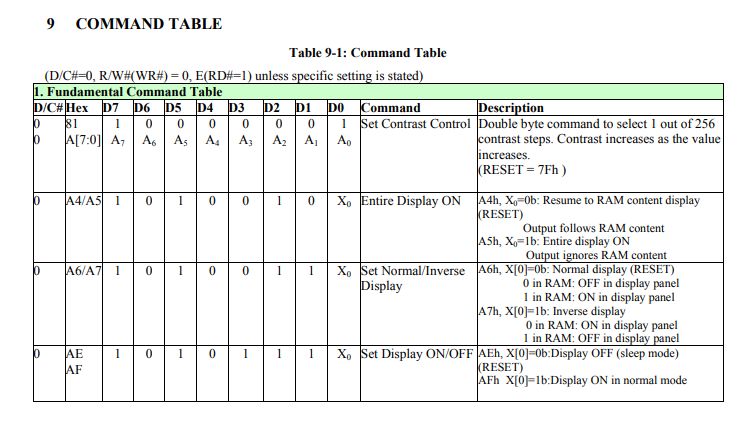

Here we have:

- commands for the display - code 0x00

- access to the pixel memory - code 0x40

A bit of stuff needs to be set up at the beginning, fortunately my 128x32 module is popular enough that I could just follow the ready-made libraries. According to the catalogue note - contrast, remapping, scan direction, inversion, offset, frequency, RAM. As far as I can see, most drivers also have this implemented as static commands executed once at module start.

In addition to this, I added a pixel send (WriteData), lit all of them for a test (0xFF - all bits lit) and alternated on/off commands, i.e. 0xAE and 0xAF, in a loop.

Code: C / C++

Of course, here it is important to remember that, for example, if we fill the pixel RAM with 0x00 bytes, the 0xAF command (turning the display on) will not do us any good, because every pixel will be off anyway.

I ran the program from my firmware command line:

backlog stopdriver SSD1306 ; startDriver SSD1306 16 20 120Result:

This confirms that, at least in some form, the commands are correctly executed and you can move on to the next stage.

First rectangles

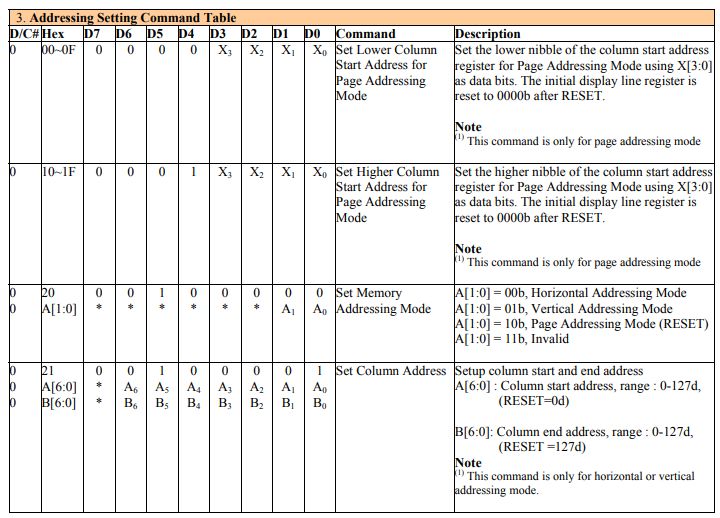

Now let's consider how the display refresh is implemented.

The simplest and the least efficient solution would be to keep the full bitmap in RAM on the microcontroller and send it all over with every change.

Here, fortunately, there is a cleverer method - we can draw on an area of pages of our choice, and the display remembers this itself.

We have 8 pages - from Page0 to Page7. In the version with a display height of 32, 4 pages are used. Each page is 128 bytes. Pages are groups of pixels, where successively we have vertical lines of 8 pixels. So by setting the first, for example, 16 bits, we create a 2x8 rectangle. If we skip every eighth bit, we create a 2x7 rectangle, and so on. The display also has the ability to change the segment mapping.

A function was created to set the position of the cursor on a given byte on one of the eight sides:

Code: C / C++

Auto-incrementing the target address, however, does not allow us to jump freely between rows and columns, so when drawing a rectangle we set the cursor separately N times. Basically, we draw it from separate lines, here aligned to memory pages (for simplicity - operation >> 3, bit-shifting 3 bits to the right, i.e. dividing by 8 to get the page index).

Code: C / C++

In addition, I take into account two filling modes - full and border, in border mode I simply test if we are at the 'edge' pixels.

Full demo:

Code: C / C++

Result:

First characters First characters

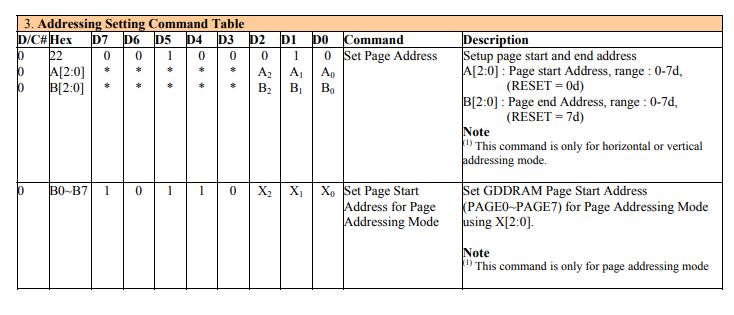

The next step is to display the text. Here again, you can take advantage of this division of memory into 8 pages and assume that you only ever draw characters on one of them. This in turn allows us to encode the characters as strings of bytes, which we send linearly to the controller, only setting the position on the selected one of the pages beforehand (SSD1306_SetPos).

For the demonstration, I used a standard 5x7 ASCII font, with no lowercase letters. The whole thing is encoded in an array:

Code: C / C++

The SSD1306_WriteChar function sends one character to the controller, this character consists of five bytes of data. Nothing more needs to be done, as we have auto-incremented the address within the selected page.

Code: C / C++

Then you can add an auxiliary function SSD1306_String, which sends consecutive characters separately.

Code: C / C++

The function for presentation remains:

Code: C / C++

Result:

Countdown Countdown Countdown

This paragraph is no longer essentially about the SSD1306, but it is still worth including here as it shows that the mechanism developed does indeed work. I first "freed" the SSD1306 by adding supporting commands to it, so that scripts from my environment could display any data on it.

Code: C / C++

I deliberately separated ssd1306_print as a function with one argument (text) and ssd1306_goto as a function with two arguments (position x y), so that I could assemble a longer string from multiple repeated calls to ssd1306_print. The position is incremented automatically, so everything looks nice, and even moving to the next line works by itself.

This is what a demonstration script looks like testing this display in my environment:

backlog stopdriver SSD1306 ; startDriver SSD1306 16 20 0x3C

ssd1306_clear 0

ssd1306_on 1

setChannel 12 0

again:

delay_s 1

ssd1306_goto 0 0

ssd1306_print "Hello "

ssd1306_print $CH12

addChannel 12 1

goto again

Result:

Summary

Operating the SSD1306 display need not be complicated at all. For basic applications, a simple software-based I2C is entirely sufficient. There is also no need for a full image buffer in RAM - pixels can be written directly to the controller's internal memory. Thanks to the ability to set the write address at the level of individual screen pages, only those areas that actually change can be refreshed. An additional advantage is the controller's built-in functions, such as quickly switching the display on and off without having to clear the memory contents.

The situation becomes slightly more complex when you want to display text. Then it is necessary to have the font data, but it still does not need to occupy RAM - it can be placed in Flash memory. The example uses a simple 5x7 ASCII font, where each character takes up 5 bytes, and the whole set covers about 60 characters, giving a total of about 300 bytes of memory. This is not much, although it may be a limitation for the smallest microcontrollers.

In summary, the SSD1306 is a very good option for projects where we want to display text, simple shapes and uncomplicated graphics. With more advanced graphics operations, however, the situation starts to get complicated and then it usually becomes necessary to use a pixel buffer in RAM, especially if you want to draw with single-pixel accuracy and not just within whole pages of memory. However, this is, in my opinion, unnecessary in many cases - from my demos you can't see that the pages dictate the positioning of the text, at first glance everything is natural and ready for production.

Have you already used displays based on the SSD1306? If so - for what applications?

Comments