Running a simple MIPS emulator in Python for ALI M3801 firmware (Hello World)

Here I will show my first attempt at building an emulator for the ALI M3801 microprocessor based on off-the-shelf Unicorn and Capstone modules. The developed program will load the contents of the Flash memory and execute it similarly to a real physical CPU, although it will not be without modifications and fixes, as Unicorn/Capstone do not implement the full logic of a particular SoC or its peripherals. In addition, the whole thing will be able to correctly handle sending data over the UART, i.e. it will emulate the register responsible for transmitting bytes over the hardware serial bus. In this way, we will get the same messages in the console that running a programme on a real ALI chip would show.

Tools used

Ghidra is an advanced reverse engineering (SRE) tool being developed by the NSA. It allows decompilation of MIPS machine code into pseudo-C code, making it much easier to analyse and understand firmware logic.

Unicorn is a lightweight, multi-platform framework for CPU emulation based on QEMU. In the project it serves as the main engine for emulating MIPS32 instructions in Little Endian mode, although in practice much of the operation (including memory access) is handled separately in my code anyway.

Capstone is an advanced disassembly engine supporting multiple architectures. It is used here to convert machine code into readable assembler instructions, which is essential for tracing and debugging them. It allows the user to see exactly what the processor is currently executing.

I will do the project in the Pyhon language.

Firmware used for demonstration

To simplify the workflow I used a ready-made 'hello world' on ALI found on GitHub - michal4132/ali_sdk . I presented this project previously here:

How to compile and run your own firmware for ALI M3801 and other tuner chips?

This firmware is characterised by the absence of precompiled modules (so-called "blobs"), which makes it easier to analyse and compare the source code to the results from the emulator. For this reason, we will use it here.

NOTE

The topic assumes a basic knowledge of terminology and I will not explain here how the processor works. I will focus here on just presenting the construction of my simple emulator.

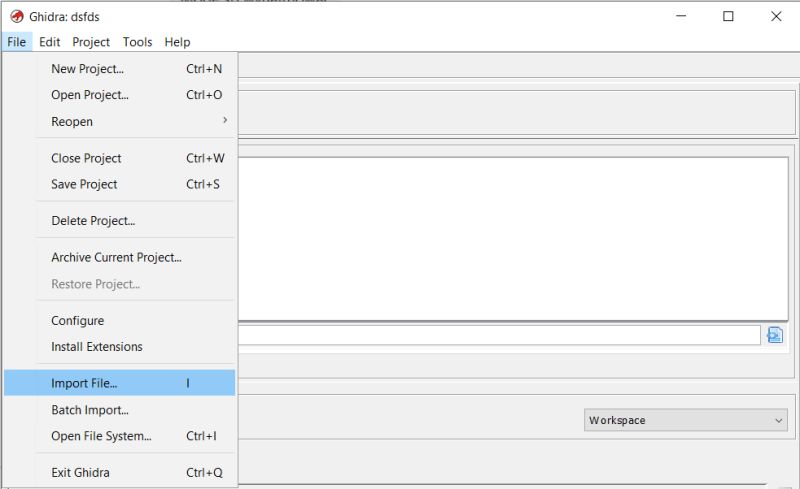

Importing firmware in Ghidr

Open Ghidra, create a new project, do File->Import File:

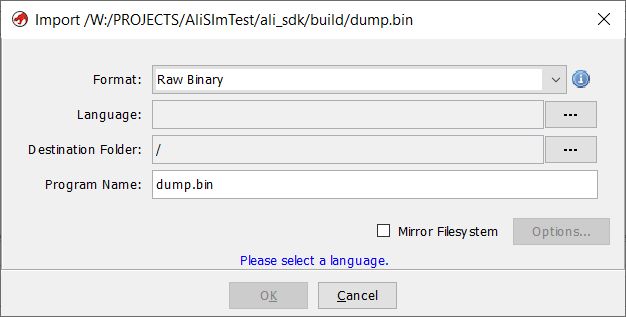

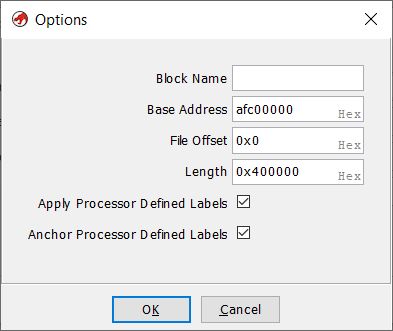

Before importing the file, you need to configure it properly.

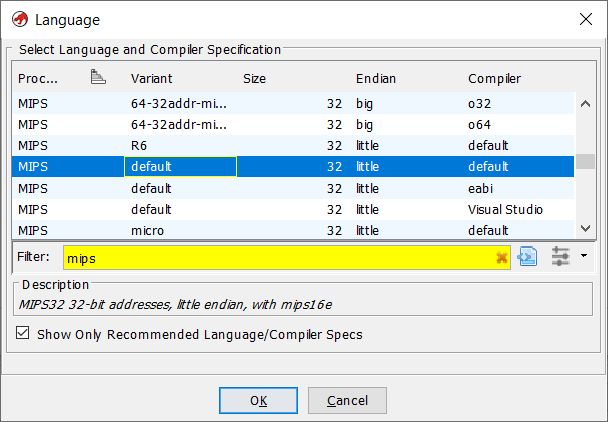

Set the architecture: MIPS Little-Endian. MIPS is a RISC architecture and Little-Endian specifies the order in which bytes are stored in memory.

Set base address: afc00000. The base address is the fixed starting address of the memory area. It serves as a reference point for further addressing of data or registers, without a correct base address the jump instructions would go to the wrong place.

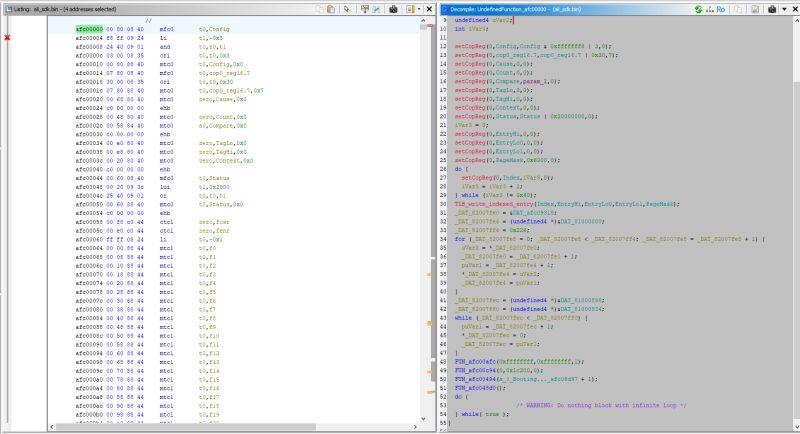

When opened, Ghidra gives us two views. The first time we have to wait for the decompilation to finish, but after that everything works smoothly.

The first view is directly the bytes of the opened file but mapped to the base address - hence the addresses start with AFC. Next to them we have the decompiled commands with their arguments.

The second view is C pseudo-code, which tries to show what the function would do in C - as much as it can. A lot of information is lost when compiling, so we don't even have variable names or the exact syntax here as it was in the source code.

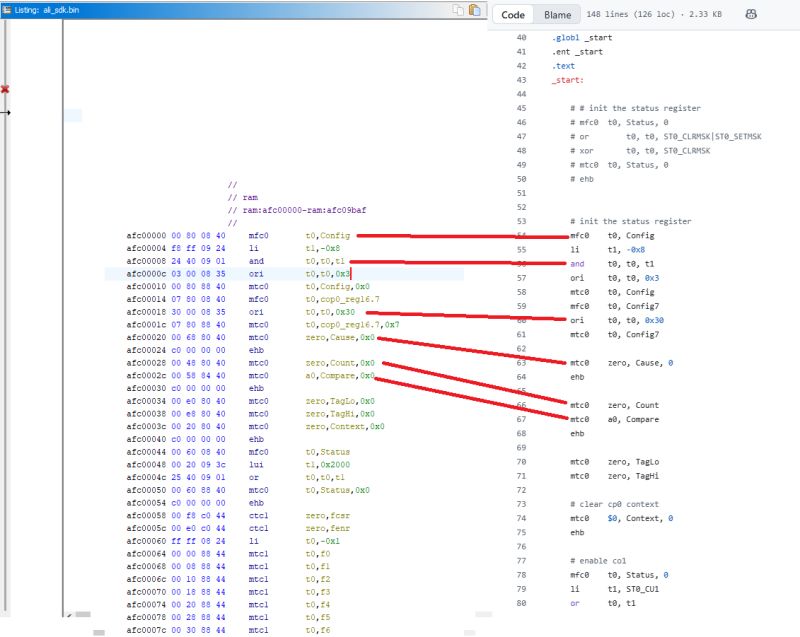

In this case we have the source code of the decompiled program, so we can compare and check. The startup routine is partly written in assembler and partly in C:

start.S:

Code: text

Continued in C:

entry.c:

Code: C / C++

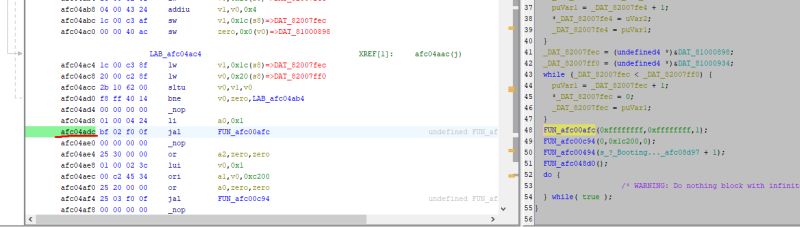

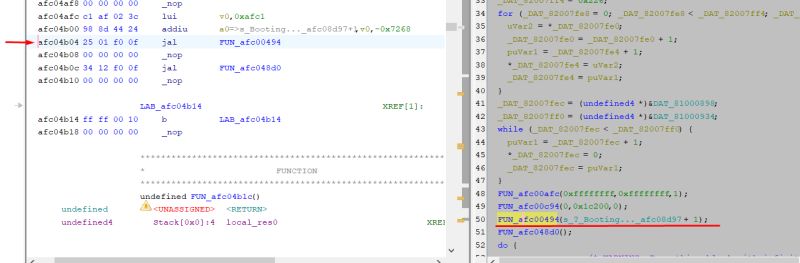

You can easily compare the two files:

You can see here, for example, that FUN_afc00afc(0xffffffff,0xffffffff,1); is uart_attach

Deassembly in Python

Let's start with the simplest one. This example shows a simple disassembly of a binary code after a given address in Python. The binary is loaded into memory at the specified base address, without running or emulating instruction execution. The Unicorn engine is only used here to map the memory, while Capstone reads the bytes from under the specified address and translates them into MIPS assembler instructions. This allows the contents of the ROM code to be quickly previewed in human-readable form and compared with what Ghidra shows.

Code: Python

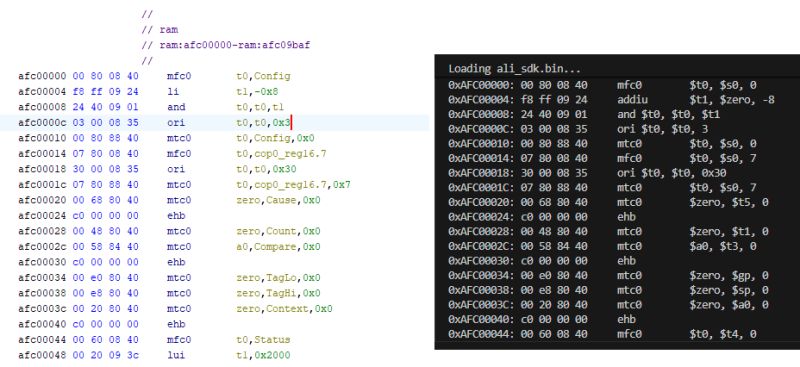

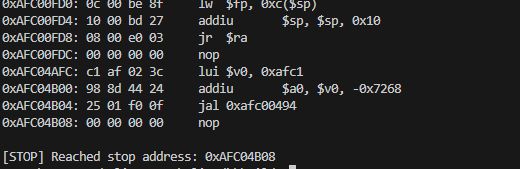

As a test, I read the first few dozen instructions. Virtually everything agrees:

The only difference is li (in Ghidra) which the Python program shows as addiu. This is because li is not an actual MIPS processor instruction, but an assembler pseudo-instruction. In firmware, there is an actual addiu (or sometimes lui + ori), which Capstone shows explicitly, while Ghidra simplifies the notation to li for readability.

First steps with the emulator

Now you can go one step further and start executing the instructions. In this example, register operations, calculations and conditional jumps will already be running. This time Unicorn will already be performing operations, although, as I found out shortly afterwards, not everything will work correctly. But one step at a time:

Code: Python

I put a limit on the program's executed instructions and compared the emulation's "footprint" with what is seen in Ghidra. The basics match, the jumps also match:

Executing first 40 instructions:

Set CP0 Status = 0x10400000

Memory Check at 0xafc00000: 00800840

Starting emulation at 0xafc00000...

0xAFC00000: 00 80 08 40 mfc0 $t0, $s0, 0

0xAFC00004: f8 ff 09 24 addiu $t1, $zero, -8

0xAFC00008: 24 40 09 01 and $t0, $t0, $t1

0xAFC0000C: 03 00 08 35 ori $t0, $t0, 3

0xAFC00010: 00 80 88 40 mtc0 $t0, $s0, 0

0xAFC00014: 07 80 08 40 mfc0 $t0, $s0, 7

0xAFC00018: 30 00 08 35 ori $t0, $t0, 0x30

0xAFC0001C: 07 80 88 40 mtc0 $t0, $s0, 7

0xAFC00020: 00 68 80 40 mtc0 $zero, $t5, 0

0xAFC00024: c0 00 00 00 ehb

0xAFC00028: 00 48 80 40 mtc0 $zero, $t1, 0

0xAFC0002C: 00 58 84 40 mtc0 $a0, $t3, 0

0xAFC00030: c0 00 00 00 ehb

0xAFC00034: 00 e0 80 40 mtc0 $zero, $gp, 0

0xAFC00038: 00 e8 80 40 mtc0 $zero, $sp, 0

0xAFC0003C: 00 20 80 40 mtc0 $zero, $a0, 0

0xAFC00040: c0 00 00 00 ehb

0xAFC00044: 00 60 08 40 mfc0 $t0, $t4, 0

0xAFC00048: 00 20 09 3c lui $t1, 0x2000

0xAFC0004C: 25 40 09 01 or $t0, $t0, $t1

0xAFC00050: 00 60 88 40 mtc0 $t0, $t4, 0

0xAFC00054: c0 00 00 00 ehb

0xAFC00058: 00 f8 c0 44 ctc1 $zero, $31

0xAFC0005C: 00 e0 c0 44 ctc1 $zero, $28

0xAFC00060: ff ff 08 24 addiu $t0, $zero, -1

0xAFC00064: 00 00 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f0

0xAFC00068: 00 08 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f1

0xAFC0006C: 00 10 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f2

0xAFC00070: 00 18 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f3

0xAFC00074: 00 20 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f4

0xAFC00078: 00 28 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f5

0xAFC0007C: 00 30 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f6

0xAFC00080: 00 38 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f7

0xAFC00084: 00 40 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f8

0xAFC00088: 00 48 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f9

0xAFC0008C: 00 50 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f10

0xAFC00090: 00 58 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f11

0xAFC00094: 00 60 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f12

0xAFC00098: 00 68 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f13

0xAFC0009C: 00 70 88 44 mtc1 $t0, $f14

Loops with emulator

Similarly, loops also work. First we have loops copying data into RAM. I added a counter to the emulator to show how many times (globally) an instruction has been executed, this allows us to visualise a little better what is happening:

Code: Python

Let's consider the first loop from this firmware:

0xAFC000E4: 40 00 04 24 addiu $a0, $zero, 0x40

0xAFC000E8: 00 00 05 24 addiu $a1, $zero, 0

0xAFC000EC: 00 60 02 24 addiu $v0, $zero, 0x6000

0xAFC000F0: 00 50 80 40 mtc0 $zero, $t2, 0

0xAFC000F4: 00 10 80 40 mtc0 $zero, $v0, 0

0xAFC000F8: 00 18 80 40 mtc0 $zero, $v1, 0

0xAFC000FC: 00 28 82 40 mtc0 $v0, $a1, 0

0xAFC00100: 00 00 85 40 mtc0 $a1, $zero, 0

0xAFC00104: 01 00 a5 24 addiu $a1, $a1, 1

0xAFC00108: fd ff a4 14 bne $a1, $a0, 0xafc00100

0xAFC0010C: 00 00 00 00 nop

0xAFC00100: 00 00 85 40 mtc0 $a1, $zero, 0 [LOOP 2]

0xAFC00104: 01 00 a5 24 addiu $a1, $a1, 1 [LOOP 2]

0xAFC00108: fd ff a4 14 bne $a1, $a0, 0xafc00100 [LOOP 2]

0xAFC0010C: 00 00 00 00 nop [LOOP 2]

0xAFC00100: 00 00 85 40 mtc0 $a1, $zero, 0 [LOOP 3]

0xAFC00104: 01 00 a5 24 addiu $a1, $a1, 1 [LOOP 3]

0xAFC00108: fd ff a4 14 bne $a1, $a0, 0xafc00100 [LOOP 3]

The loop section (afc00100 - afc00108) repeats 64 times.

This is the loop from entry.S:

Code: text

This can be compared to the source code:

Code: C / C++

This is what the end of the loop looks like:

0xAFC00100: 00 00 85 40 mtc0 $a1, $zero, 0 [LOOP 63]

0xAFC00104: 01 00 a5 24 addiu $a1, $a1, 1 [LOOP 63]

0xAFC00108: fd ff a4 14 bne $a1, $a0, 0xafc00100 [LOOP 63]

0xAFC0010C: 00 00 00 00 nop [LOOP 63]

0xAFC00100: 00 00 85 40 mtc0 $a1, $zero, 0 [LOOP 64]

0xAFC00104: 01 00 a5 24 addiu $a1, $a1, 1 [LOOP 64]

0xAFC00108: fd ff a4 14 bne $a1, $a0, 0xafc00100 [LOOP 64]

0xAFC0010C: 00 00 00 00 nop [LOOP 64]

0xAFC00110: 02 00 00 42 tlbwi

0xAFC00114: 00 00 00 00 nop

0xAFC00118: 01 82 1d 3c lui $sp, 0x8201

0xAFC0011C: 00 80 bd 27 addiu $sp, $sp, -0x8000

0xAFC00120: c0 af 08 3c lui $t0, 0xafc0

0xAFC00124: 04 4a 08 25 addiu $t0, $t0, 0x4a04

0xAFC00128: 08 00 00 01 jr $t0

0xAFC0012C: 00 00 00 00 nop

0xAFC04A04: d0 ff bd 27 addiu $sp, $sp, -0x30

0xAFC04A08: 2c 00 bf af sw $ra, 0x2c($sp)

Subsequent loops:

0xAFC04A68: 14 00 c4 af sw $a0, 0x14($fp) [LOOP 9]

0xAFC04A6C: 00 00 63 8c lw $v1, ($v1) [LOOP 9]

0xAFC04A70: 00 00 43 ac sw $v1, ($v0) [LOOP 9]

0xAFC04A74: 18 00 c2 8f lw $v0, 0x18($fp) [LOOP 9]

0xAFC04A78: 01 00 42 24 addiu $v0, $v0, 1 [LOOP 9]

0xAFC04A7C: 18 00 c2 af sw $v0, 0x18($fp) [LOOP 9]

0xAFC04A80: 24 00 c2 8f lw $v0, 0x24($fp) [LOOP 10]

0xAFC04A84: 18 00 c3 8f lw $v1, 0x18($fp) [LOOP 10]

0xAFC04A88: 2b 10 62 00 sltu $v0, $v1, $v0 [LOOP 10]

0xAFC04A8C: f1 ff 40 14 bnez $v0, 0xafc04a54 [LOOP 10]

0xAFC04A90: 00 00 00 00 nop [LOOP 10]

0xAFC04A54: 10 00 c3 8f lw $v1, 0x10($fp) [LOOP 10]

0xAFC04A58: 04 00 62 24 addiu $v0, $v1, 4 [LOOP 10]

0xAFC04A5C: 10 00 c2 af sw $v0, 0x10($fp) [LOOP 10]

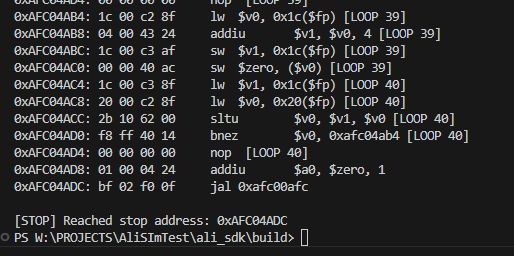

Stopping at an instruction

Another useful mechanism that I have decided to implement is to stop the program on a command with a given address. This allows me to easily check if the executed program reaches a certain point, whose address I find in Ghidra. You could say that this is a simple breakpoint, like in a debugger. For the moment, it is enough for me to define the STOP_INSTR variable in the code.

Code: text

This is where Ghidra came in handy again. There I selected the address at which I want to stop the execution of the commands (afc04adc) and then verified the program trace to make sure everything was correct. This is very convenient and useful for testing and verifying that the program is running correctly.

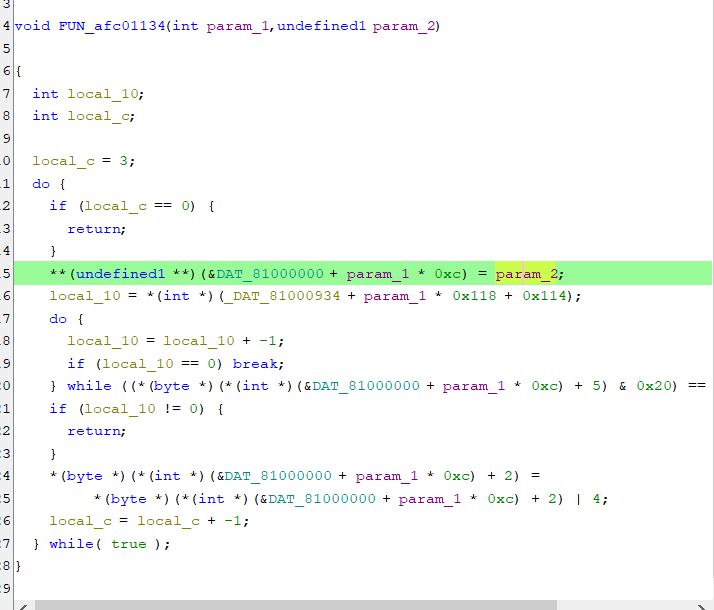

Fine UART initialization fix

The program, prepared in this way, was already reaching uart_set_mode, but was showing an access error when trying to write data to the UART register.

Code: C / C++

These registers were not mapped to memory:

Code: C / C++

I had to add their mapping:

Code: Python

After this change, the emulator gets as far as 0xAFC04B04, which is where the text data will be sent:

What's more, the function itself from the display also executes. I set the endpoint right after it, and there are no errors.

Interrogating the text display

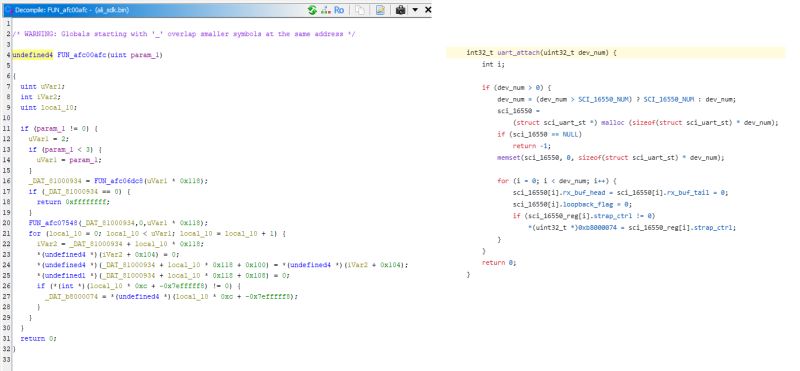

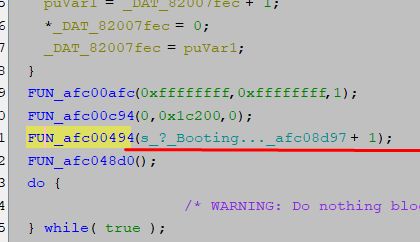

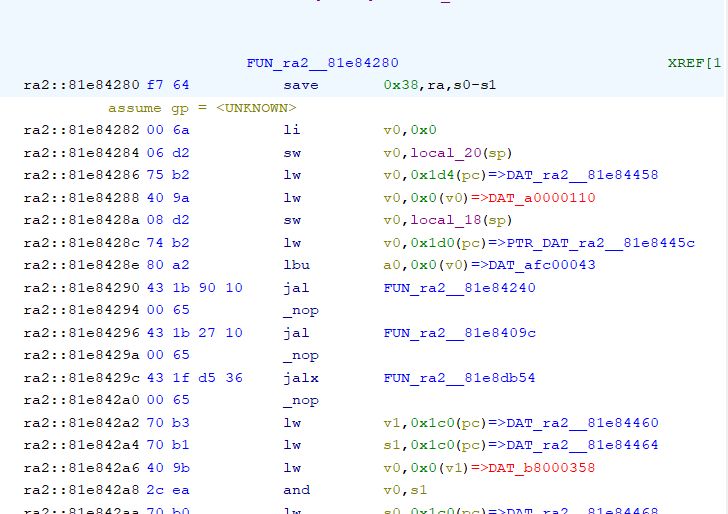

Unfortunately, full support for text display would require emulation of the UART along with reading its register used to send data. For now, we'll keep it simple and just capture the printf function itself. In Ghidra, it is easy to trace it because its argument is a character string:

We can intercept its call and artificially skip its execution:

Code: Python

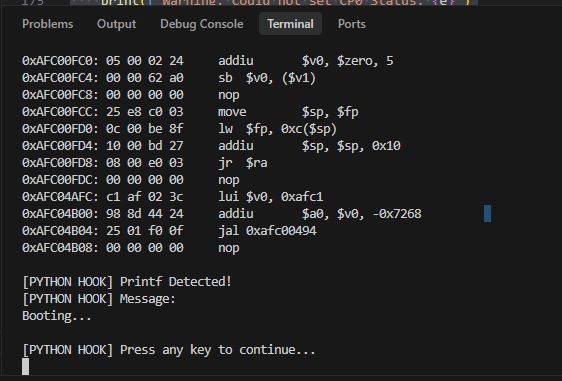

Result:

Well, yes, but now printf-style formatting of variables doesn't work. No wonder, our Python function displays blindly. Maybe it's better to look at the printf source code:

Code: C / C++

The formatting can be emulated and we plug in fwrite though. Here, however, was a problem that took me a long time, but I will keep it to a minimum for you. It seems that the execution of the sb/sw commands , i.e. the instructions responsible for writing to memory, is not working.

I have implemented their manual execution:

Code: Python

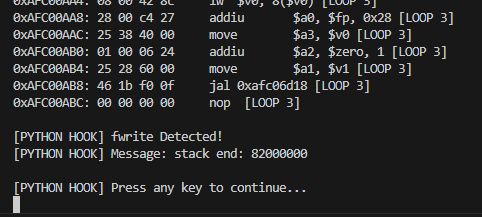

And this is what the hook on fwrite looks like:

Code: Python

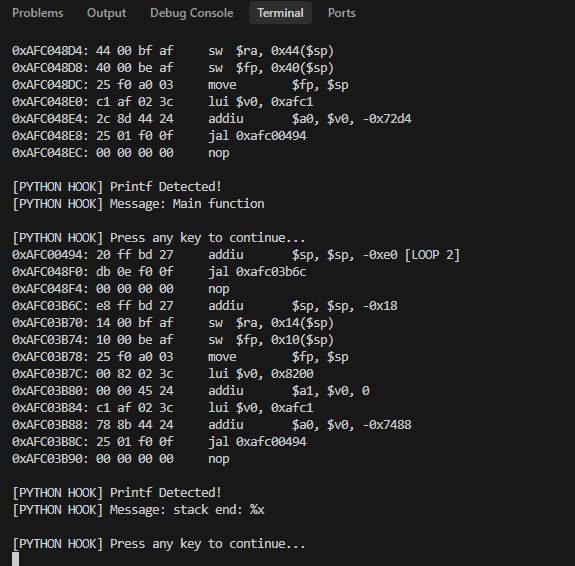

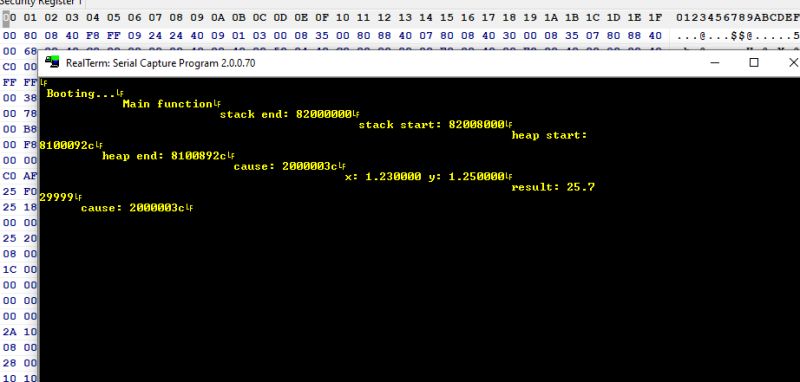

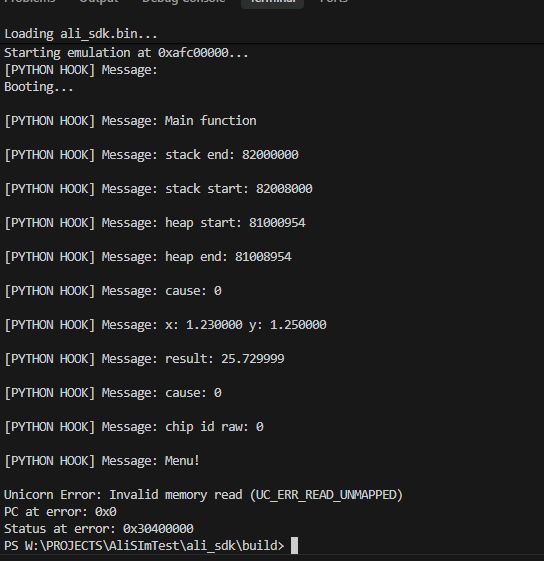

Result:

Agrees with the one from the CPU:

All text, after turning off showing instructions:

Not too bad, even operations on floating point numbers work.

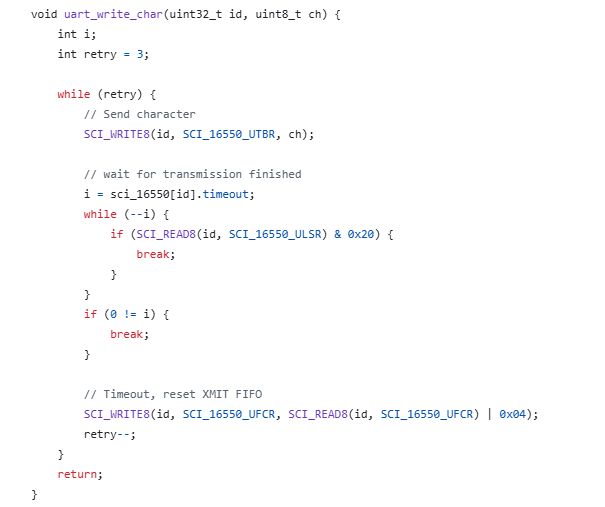

Faster UART emulation

Capturing kprintf or there fwrite is nice for testing, but not at all practical. The address of these functions can probably change with each compilation. It is true that at compile time you can force a function to have a given address, but I wouldn't expect that here.

The UART needs to be handled better - you need to know where the hardware UART register is and it's from there that you read the data.

Fortunately we already have this information - it can be found in many SDKs on GitHub.

The UART addresses are:

Code: C / C++

The register for the character is:

Code: C / C++

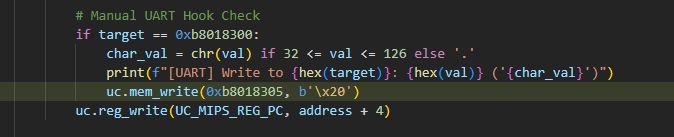

However, let us focus on the posting itself. We can easily conclude that all we need to do is capture the write to this address and display it as output from the UART.

This is where a small technical problem arose, because as it turned out, Unicorn does not execute some of the commands correctly, so I had to implement them manually:

Code: Python

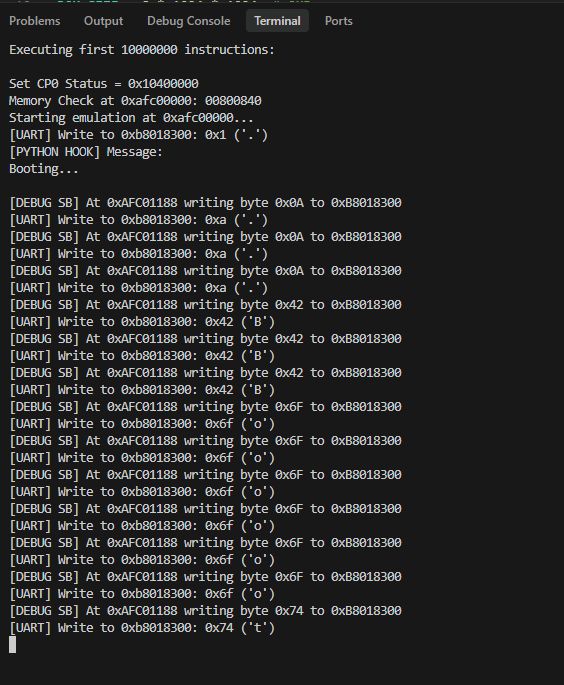

Only then are the operations executed.

Eventually the UART sends the data, but something is wrong. The data is repeated three times. An explanation of this will be found below:

The firmware checks to see if the UART acknowledges the sending of the data and, if not, performs the transmission again. All in a loop, in a blocking manner. So we still need to include the transmission acknowledgement flag.

To do this, we need to simulate bit 0x20 of SCI_16550_ULSR. We can do this as soon as a byte is sent. Very simple:

Full code:

Spoiler:

Code: Python

As of now, the UART is sending data correctly.

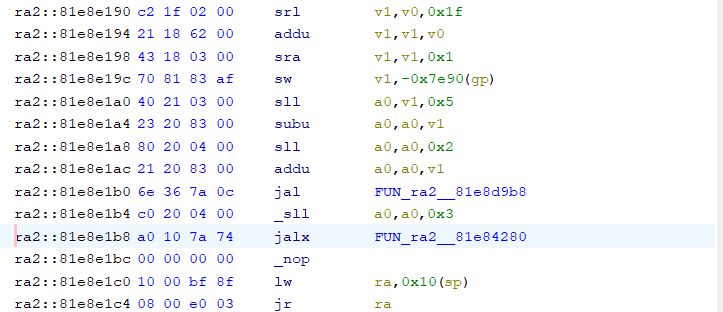

Problem to be solved in the next topic

The main problem that is still to be solved is the 16-bit MIPS commands, these occur sporadically on the original upload from ALI:

And moments later:

The emulator used does not seem to support this, so there will be further combinations.

Summary Summary

This managed to run Hello world completely as if the target CPU was doing it - no shortcuts or simplifications. My program emulates the base of the ALI M3801 and is able to show what would be sent via UART 1.

The whole thing turned out to be more difficult than I thought, as I had to reimplement some of the commands myself to get the read/write to work correctly, and on addresses as MIPS sees them - Unicorn does not implement KSEG0/KSEG1 segmentation and masks the address to 29 bits, treating it as a physical address. This is well demonstrated in this example:

Spoiler:

0xAFC00E18: 07 00 09 a1 sb $t1, 7($t0)

0xAFC00E20: 03 40 29 35 ori $t1, $t1, 0x4003

0xAFC00E24: 00 00 09 ad sw $t1, ($t0)

0xAFC00E28: 0c 00 09 24 addiu $t1, $zero, 0xc

0xAFC00E2C: 04 00 09 a1 sb $t1, 4($t0)

0xAFC00E30: 00 a0 0a 3c lui $t2, 0xa000

0xAFC00E34: a0 26 4a 35 ori $t2, $t2, 0x26a0

0xAFC00E38: 00 00 49 8d lw $t1, ($t2)

[!] INVALID MEMORY ACCESS

Type: 19

Address: 0x000026A0

Size: 4

PC: 0xAFC00E38

Unicorn Error: Invalid memory read (UC_ERR_READ_UNMAPPED)

PC at error: 0xafc00e38

0xAFC00E18: 07 00 09 a1 sb $t1, 7($t0)

0xAFC00E20: 03 40 29 35 ori $t1, $t1, 0x4003

0xAFC00E24: 00 00 09 ad sw $t1, ($t0)

0xAFC00E28: 0c 00 09 24 addiu $t1, $zero, 0xc

0xAFC00E2C: 04 00 09 a1 sb $t1, 4($t0)

0xAFC00E30: 00 a0 0a 3c lui $t2, 0xa000

0xAFC00E34: a0 26 4a 35 ori $t2, $t2, 0x26a0

0xAFC00E38: 00 00 49 8d lw $t1, ($t2)

[!] INVALID MEMORY ACCESS

Type: 19

Address: 0x000026A0

Size: 4

PC: 0xAFC00E38

Unicorn Error: Invalid memory read (UC_ERR_READ_UNMAPPED)

PC at error: 0xafc00e38

The code shows 0xa00026a0 and the emulator wants access to 0x000026A0. Maybe I should tweak this to hold the physical conversion, but that's in the next section. Initially I thought a triple mapping into the same memory section would suffice:

Code: Python

but the operations weren't performing anyway - at this point it's not clear to me what I was doing wrong.

Follow up soon, all suggestions welcome - this is my first approach to emulation.

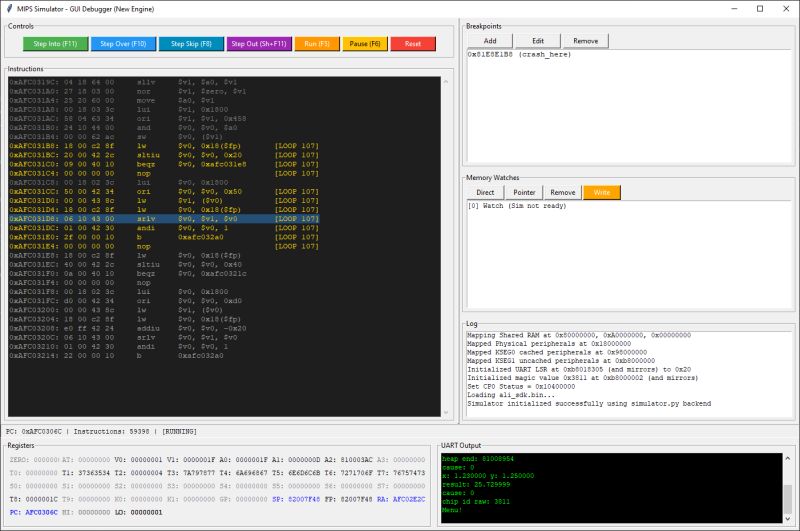

Here's a little preview of the next topic:

Comments

A small update as to the fun of emulating. As I suspected, I'm stuck on those 16-bit instructions for now. Without them, I won't even for a good while start executing the actual bootloader from the... [Read more]

Thanks for this description, I've been wanting to get on with it myself to analyse another decoder on MIPS too. You made it very easy for me to go further by showing the base. Cool that you mapped the... [Read more]

At the moment the problem is with 16-bit inserts. Capstone/Unicorn doesn't seem to support them (I couldn't get it to do so), so I have to combine manually. Unfortunately they are repeated repeatedly in... [Read more]

MIPS distinguishes (assuming the core supports this at all) whether it should interpret an instruction as 16bit or 32bit by looking at the youngest bit of the instruction address. Jumping to a function... [Read more]